So much talk about the

ailments that have left Europe lagging behind for more two decades now, when

precisely the opposite was expect when the treaty of Maastricht was

signed in 1992. The first decade of the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) was marked by low growth and high unemployment; This was followed by another period of low growth but a slightly better unemployment outlook, which coincided with the introduction of the Euro. But it all came crashing down with the great recession (2007) and a new period of ultra-low economic growth and even higher unemployment seems to have become the norm in the third decade under the single currency.

Euro area countries started to surrender their monetary sovereignty in 1990 when following the presentation of the Delors report it was decided to start the first stage (out of three) of the monetary union that would culminate in 2002 with the physical introduction of Euro currency. A major step was taken in 1992 with the signature of the Maastricht Treaty (Treaty on European Union) that formally introduced the prohibition of the central banks "financing” the government as is made clear by article 104:

Euro area countries started to surrender their monetary sovereignty in 1990 when following the presentation of the Delors report it was decided to start the first stage (out of three) of the monetary union that would culminate in 2002 with the physical introduction of Euro currency. A major step was taken in 1992 with the signature of the Maastricht Treaty (Treaty on European Union) that formally introduced the prohibition of the central banks "financing” the government as is made clear by article 104:

"1.Overdraft facilities or any other

type of credit facility with the ECB or with the central banks of the

Member States (hereinafter referred to as “national central banks”) in favour

of Community institutions or bodies, central governments, regional, local or

other public authorities, other bodies governed by public law, or public

undertakings of Member States shall be prohibited, as shall the purchase

directly from them by the ECB or national central banks of debt instruments."

(Council Regulation (EC) No 3603/93 of

13 December 1993 that came into force at the same time as the Article

104 to clarify some definition above)

Monetary sovereignty was

further severed with the establishment of the European and Monetary Institute,

forerunner of the European Central Bank (ECB) and the process of surrender of

monetary sovereignty would culminate with the introduction of the single

currency- the Euro- and the conduit of a single monetary policy by the ECB. With

the introduction of the Euro, the countries that adhered to it, surrendered

completely their monetary sovereignty by

transferring the power of issuance of currency to a supranational authority,

the ECB, but contrary to other monetary unions where a single currency

was adopted, Us or Swiss, no Central (or Federal) Government was

created, as such the Eurozone is a particular case of monetary union "one

money, (too) many governments".

For the countries themselves

it is as if they became users of a foreign currency, akin to a dollarization,

but contrary to this, they gave up their own currency for good. This raises two

types of problems: first, by surrendering their monetary sovereignty or the

power to create money, they have become effectively non-sovereign states,

similar to a local authority; second, by separating their fiscal and monetary

authorities, they have given up their power to pursue policies to achieve full

employment. The European nations effectively become non-sovereign nations. similar to US states, but with no Federal government to back them.

The implications of this

particular arrangement must not have been completely understood at the time, at

least by the countries that adhered to it, though others, namely the UK, Sweden and

Denmark, if they didn't understand it back then they seem to get it

quite well now, as they decided to stay out of the monetary union. But even

today, when the flaws have been exposed, the implications of such a unique

construction are not fully comprehended. Wynne Godley, on the contrary, understood quite

well the implications of having a monetary union with an independent Central

Bank and no Central government when he wrote his article " Maastricht and

all that" in 1992. In it, he starts by expressing the view that modern

economies are not self-adjusting systems and as such they need some management:

"I think that the central

government of any sovereign state ought to be striving all the time to

determine the optimum overall level of public provision, the correct overall

burden of taxation, the correct allocation of total expenditures between

competing requirements and the just distribution of the tax burden. It must

also determine the extent to which any gap between expenditure and taxation is

financed by making a draft on the central bank and how much it is financed by

borrowing and on what terms. The way in which governments decide all these (and

some other) issues, and the quality of leadership which they can deploy, will,

in interaction with the decisions of individuals, corporations and foreigners,

determine such things as interest rates, the exchange rate, the inflation rate,

the growth rate and the unemployment rate."

However, precisely the

opposite view, one that sees government intervention as the "source of all

evil, had gained prominence following the "troubled" decade of

the 80's and this vision was undoubtedly behind the construction of the

European Monetary Union as Wynne Godley rightly observed:

"I am driven to

the conclusion that such a view – that economies are self-righting organisms

which never under any circumstances need management at all – did indeed

determine the way in which the Maastricht Treaty was framed. It is a crude and

extreme version of the view which for some time now has constituted Europe’s

conventional wisdom (though not that of the US or Japan) that governments are

unable, and therefore should not try, to achieve any of the traditional goals

of economic policy, such as growth and full employment. All that can

legitimately be done, according to this view, is to control the money supply

and balance the budget."

This view is clearly

expressed further in the single mandate of the ECB and the Maastricht Criteria

that had to be met by the European countries that joined the

Euro. While the Federal Reserve has a dual mandate: (1) maximum employment; and (2) stable prices; The ECB single mandate is to maintain price stability

within the Eurozone, which at times might be at odds with more important

economic goals, like reducing unemployment. However, it is

mainly in the Maastricht

criteria that this view was enunciated with the "sound" and

"sustainable" public finances criteria that translate into the prohibition of government deficits exceeding

3% of GDP and government debt exceed 60% of GDP.

If during periods of

economic expansions the differences between sovereign and non-sovereign

governments are not always evident, during periods of recession this are made

clear. While the sovereign government can spend without regard of revenue, the

non- sovereign government ability to spend is dependent on tax revenues and its

ability to borrow, both of which tend to fall during recessions and increase

during expansions as such leading non-sovereign governments to act

pro-cyclically. i.e increasing spending during expansions and cutting during

recessions as pointed out by Randall Wray:

Sovereign governments are

able to deficit spend as necessary to climb out of recession and to restore

full employment. Lack of will, not lack of financial where-with-al, is the constraint. Nonsovereign

governments are constrained by revenues and ability to borrow, the latter of

which is a function of market assessment of credit risk. They can provide a

more favorable environment for private spenders (“structural

adjustment”—including reduction of labor market “frictions” such as minimum

wage laws) in the hope that this might increase nongovernmental demand, but

they may not be able to increase demand directly as needed should this fail.

Their own ability to spend will necessarily be pro-cyclically biased: not

only does their tax revenue rise in good times, but market assessment of their

credit-worthiness will also improve in expansion.

The outcome of this

particular institutional arrangement is all too evident as it has resulted in

two decades of low or ultra-low economic growth and high levels of unemployment. It all started with the establishment of the the European Monetary System (EMS) in 1979, whereby the countries of the European Economic Community (EEC) decided to link their currencies to avoid large fluctuations of the exchange rate. Even though no currency was officially designated as the anchor of the system, soon the Deutsche Mark would emerge as the reference and with it the Bundesbank as the principal Central Bank of the system. Given the anchor status of the Deutsche Mark only Germany was able to set monetary policy freely, with all the other countries having to follow its lead in order to keep the peg. The EMS was in part responsible for the severity of the early 90's

recession in Europe, as this was certainly more severe there than in other developed

countries, but it is the response to this crisis that started to set apart

sovereign from non-sovereign nations.

Following Germany's reunification, inflationary pressures started to build up in Germany and this led the Bundesbank to hike interest rates from a low of 2.5% in the middle of 1998 to 6% at the end of 1989 and a further increase to 8.5% at the end of 1992. In the context of the reunification and the slowdown of the global economy, the interest rate hike by the Bundesbank seems an overreaction. The economy had grown more than 5% in 1990 and 1991 but the rest of the world was in recession or at least slowing down; as such, a slowdown should have been expected. Inflation running around 3%, hardly out of control. Even unemployment, that rose from 5% in 1990 to 5.5% in 1991, could hardly be said to be high when compared to most of its neighbours. The budget deficit running at 3% was remarkably low for a country that had taken on a poorer country.

Nevertheless, in order to keep the deficit under control in the face of the increased expenditure with the reunification, some fiscal consolidation had to be made. And so, as a paper by Jörg Bibow defends, the German government under the command of the Bundesbank embarked on fiscal consolidation in a pro-cyclical and inexplicably aggressive way, which was not only in conflict with economic theory but also with the best practices observed in other more successful countries. In addition, the Bundesbank imposed tight money of an exceptional length and degree, magnifying rather than compensating the depressive effects of fiscal policy.

Following Germany's reunification, inflationary pressures started to build up in Germany and this led the Bundesbank to hike interest rates from a low of 2.5% in the middle of 1998 to 6% at the end of 1989 and a further increase to 8.5% at the end of 1992. In the context of the reunification and the slowdown of the global economy, the interest rate hike by the Bundesbank seems an overreaction. The economy had grown more than 5% in 1990 and 1991 but the rest of the world was in recession or at least slowing down; as such, a slowdown should have been expected. Inflation running around 3%, hardly out of control. Even unemployment, that rose from 5% in 1990 to 5.5% in 1991, could hardly be said to be high when compared to most of its neighbours. The budget deficit running at 3% was remarkably low for a country that had taken on a poorer country.

Nevertheless, in order to keep the deficit under control in the face of the increased expenditure with the reunification, some fiscal consolidation had to be made. And so, as a paper by Jörg Bibow defends, the German government under the command of the Bundesbank embarked on fiscal consolidation in a pro-cyclical and inexplicably aggressive way, which was not only in conflict with economic theory but also with the best practices observed in other more successful countries. In addition, the Bundesbank imposed tight money of an exceptional length and degree, magnifying rather than compensating the depressive effects of fiscal policy.

The paper goes even further

to challenge the assumed view that the relative underperformance of the German

economy in the period that followed the reunification was a direct result of

it, to advance that the poor performance was rather a result of the monetary

and fiscal policies implemented by the German government and the Bundesbank in the period:

"This paper challenges

the view that the marked deterioration in public finances since unification,

and western Germany's exceptionally poor performance more generally, might be

largely attributed to unification. Specifically, this paper challenges the

view, implicit in the Bundesbank's above assessment, that the rise in public

indebtedness reflects that the virtuous course of fiscal consolidation might

have been adopted either belatedly or not firmly enough. Instead, it is argued

here that ill-timed and inexplicably tight fiscal policies in conjunction with

tight monetary policies of an exceptional length and degree caused the severe

and protracted de-stabilization of western Germany in the first place. The key

result is that Germany's dismal recent record must not be seen as a direct and

apparently inevitable result of unification, but as the perfectly unnecessary

consequence of stability-oriented macro policies conducted under the

Bundesbank's dictate."

The result was a recession in 1993 and a rise in unemployment that would

only start to decline in 1997. But the Bundesbank "fanaticism" had

implications well beyond its borders, due to the anchor position of the

Deutsche Mark in the European

Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM). While Germany was free to set its monetary policy and for that

matter its fiscal policy, the other countries had limited control over their

monetary policy as it was used mainly to control the exchange rate. This

effectively prohibited the other participating countries to react by cutting

interest rates to counter the deteriorating economic conditions.

Wynne Godley highlighted the need for cooperation at the height of the crisis:

"The political implications of this are becoming frightening. Yet the interdependence of the European economies is already so great that no individual country, with the theoretical exception of Germany, feels able to pursue expansionary policies on its own, because any country that did try to expand on its own would soon encounter a balance-of-payments constraint. The present situation is screaming aloud for co-ordinated reflation, but there exist neither the institutions nor an agreed framework of thought which will bring about this obviously desirable result."

Without coordination each country was to fend for itself and this was the main cause of the European Currency Crisis of 1992- 1993. The short lived experience of the UK in the ERM is illustrative of the problems with the mechanism. To counter inflation pressures in 1988 the UK started to increase its interest rate from a low of 8% in 1988 to a high of 14.8% in 1990 when it joined the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM). Initially rates fell steadily to 10% but on 16 September 1992 as the pound came under attack by speculators, the British government increased the rates to 12% and promised to raise them to 15% in order to maintain the exchange rate. But as speculators, chief among them George Soros, kept on selling the pound the government eventually decided to abandon the ERM and regain its monetary sovereignty again on what would later be known as the Black Wednesday.

By the end of the year interest rates had been set below 6% but more important the budget deficit was allowed to increase up to 7.5% of GDP in 1993 and it wasn't until 1997 that it went below 3%. Not surprisingly, the economy started to rebound and in 1993 it grew at a rate of 3.5%. It would peak at an astonishing 5% in the next year and kept on growing above 2% until the Great Recession in 2008. Good news didn't stop there as unemployment peaked in 1993 and went all the way down to 5%, levels not seen since the 70's. By regaining it economic sovereignty, the UK unleashed one of the more extraordinary periods of growth, 16 years non-stop, accompanied by 15 years of decreasing or low unemployment. One can even speculate what would have happen if the government instead of having balanced budgets from 1998 to 2001 had embarked on a programme of infrastructure spending, probably the economic growth would have been higher and more balanced and the recent recession wouldn't have been so serious; But surely the UK could have first class infrastructure, a far cry from today’s crumbling and overcrowded roads, railways and airports . Anyway, no wonder that "Black Wednesday" is now dubbed "Bright Wednesday". Probably these golden years owe more to George Soros and a lot less to the supply-side economic reforms of the Thatcher years.

On the other side of the channel, on the other hand, things haven't looked bright for a long time. After

the attack on the British Pound the speculators went after the Italian Lira,

the Portuguese Escudo and the Spanish Peseta until eventually they pulled out

of the ERM (lira) or devalued their currencies. Last but not least they went

after the French Franc, but here the fight was different as the Banque de France had the help of the Bundesbank.

Initially they were successful with the intervention in the forex market by

buying Francs and selling Marks but this just bought some time as the French

economic situation deteriorated further.

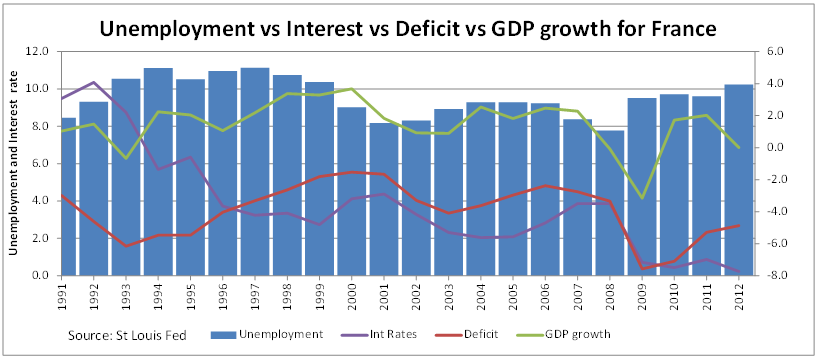

With the economy decelerating and unemployment rising, France needed to lower interest rates to stimulate the economy but precisely the opposite happened as France had to increase rates to defend the Franc (see spike in rates from 1992 to 1993 in the graph Interest Rates, discount rates above). Between 1992 and 1993 rates were increased several times and remained above 10% until they eventually gave up defending the exchange rate which would then lead to the Brussels Compromise which relaxed the fluctuations band to 15%. After regaining part of its monetary sovereignty, France immediately cut its rates and by the end of the year they had fallen below 7%. Although the economy got out of recession to grow 2.2% in 1994 it decelerated in the following years to 2.0% and 1.1% as interest rates were increased in 1995 again. On the unemployment side, however, the things never really rebounded. After the small decrease in 1995 it started to increase again and it has never really recovered until today.

Contrary to the UK, France started to consolidate its budget before unemployment had started to fall. This happened because at the time a major change was taking place; The Maastricht treaty entered into force on 1 November 1993 and with it the Maastricht criteria, in particular the prohibition of government deficits exceeding 3% of GDP and government debt exceeding 60% of GDP. For France that in 1993 had a deficit of 6.2% of GDP, this meant that it had to start consolidating its budget in the middle of a recession with very high unemployment as such, effectively, "locking in" its unemployment rate. While it kept on reducing the deficit until it reached 1.7% in 1999 when the Euro was introduced, its unemployment rate kept on rising until 1998. From 1998 to 2001 it decreased slightly but resumed its path after the introduction of the Euro.The same can be said for Italy, just add that the consolidation started even sooner and was more severe than in France, but this was compensated by a great decrease in interest rates.

With the economy decelerating and unemployment rising, France needed to lower interest rates to stimulate the economy but precisely the opposite happened as France had to increase rates to defend the Franc (see spike in rates from 1992 to 1993 in the graph Interest Rates, discount rates above). Between 1992 and 1993 rates were increased several times and remained above 10% until they eventually gave up defending the exchange rate which would then lead to the Brussels Compromise which relaxed the fluctuations band to 15%. After regaining part of its monetary sovereignty, France immediately cut its rates and by the end of the year they had fallen below 7%. Although the economy got out of recession to grow 2.2% in 1994 it decelerated in the following years to 2.0% and 1.1% as interest rates were increased in 1995 again. On the unemployment side, however, the things never really rebounded. After the small decrease in 1995 it started to increase again and it has never really recovered until today.

Contrary to the UK, France started to consolidate its budget before unemployment had started to fall. This happened because at the time a major change was taking place; The Maastricht treaty entered into force on 1 November 1993 and with it the Maastricht criteria, in particular the prohibition of government deficits exceeding 3% of GDP and government debt exceeding 60% of GDP. For France that in 1993 had a deficit of 6.2% of GDP, this meant that it had to start consolidating its budget in the middle of a recession with very high unemployment as such, effectively, "locking in" its unemployment rate. While it kept on reducing the deficit until it reached 1.7% in 1999 when the Euro was introduced, its unemployment rate kept on rising until 1998. From 1998 to 2001 it decreased slightly but resumed its path after the introduction of the Euro.The same can be said for Italy, just add that the consolidation started even sooner and was more severe than in France, but this was compensated by a great decrease in interest rates.

No wonder then that

unemployment in the main Euro Area economies was not only higher during the

early 90's recession but remained significantly higher than the European

Economies that decided to stay out of the monetary union until today. United Kingdom and Denmark have opt-out

clauses while Sweden has decided to stay out even though it has committed to

join. Denmark, however, has decided to join the ERM II in 1999 and as such its

currency is pegged to the Euro with a floating margin of 2.25% either way.

While unemployment in Denmark and the UK went down steeply from 1993, when

monetary sovereignty was regained, in

the Euro Area it continued to increase until 1994, where it stood more or less

unchangeable until 1997. It started to come down then, albeit very slowly. The

unemployment in Sweden, who was at the time dealing with the aftermath of its

own banking crisis, took a little longer to start to fall but once it was under

way the fall was abrupt. Most of all it seems that the golden age

of global growth that started in the mid-to-late 1990s just passed by the Euro

Area and there's nothing to show for it. It was supposed to have been a time of

prosperity but it all ended up in disappointment. The Eternal Recession Mechanism seems to be a more appropriate label for the ERM. High unemployment was the

price to pay for the loss of sovereignty.

The IMF recognized that

unemployment was particularly high in the Eurozone in a paper dated 1999 under

the title of Chronic

unemployment in the Euro area: causes and cures

"Despite some

modest improvement since 1997, persistently high unemployment remains a major

problem in Europe, especially among most of the economies that entered monetary

union on January 1, 1999." But surprisingly (or not) they were not

able to put two and two together as they defended that unemployment was the result of labor

market rigidities and a series of adverse shocks since the early 1970s- the

denominated "dominant view": " The "dominant

view" outlined above appears consistent with the observed developments.

The secular rise of unemployment in Europe has been concentrated in periods of

slow growth or recession when output and demand fell below potential. The

failure of employment to increase symmetrically during the subsequent

recoveries - in contrast to the experience of the United States- coincided with

real wage increases picking up well before unemployment had returned to its previous

trough"

This view has ushered more

than a decade of useless papers and recommendations under the label of “structural

reforms". However, in Japan, arguably one of the most rigid labour

markets in the developed world,

unemployment has been kept low despite the explosion of a massive asset price

bubble in the early 90's and weak

growth for more than two decades now. Japan responded by aggressively cutting the

interest rates and steadily increasing its deficit as growth faltered. From 1991 to 1996 rates were cut from 6% to

less than 1% while budget deficit as percentage of GDP increased from less than

1% in 1992 to 8% in 2000 as unemployment increased.

Certainly Japan has had lacklustre growth since the burst of its bubble - the famous lost decade - but surely other causes, chief among them population decline, have combined to bring about a very challenging situation. Nevertheless, Japan has fared better than other countries in the same situation; at least no one can blame the government for not acting decisively in supporting its economy. The Japanese Central Bank even went to the extreme of experimenting with unconventional monetary policies - quantitative easing- to stimulate the economy. Above all it has kept unemployment low, which by itself is extraordinary achievement in a time where high unemployed has become a new normal.

Certainly Japan has had lacklustre growth since the burst of its bubble - the famous lost decade - but surely other causes, chief among them population decline, have combined to bring about a very challenging situation. Nevertheless, Japan has fared better than other countries in the same situation; at least no one can blame the government for not acting decisively in supporting its economy. The Japanese Central Bank even went to the extreme of experimenting with unconventional monetary policies - quantitative easing- to stimulate the economy. Above all it has kept unemployment low, which by itself is extraordinary achievement in a time where high unemployed has become a new normal.

No comments:

Post a Comment