If in the 90's most of the governments in the Eurozone were partially constrained in their use of monetary and fiscal policies, during the Eurozone crisis they felt even more restrained as now they have completely forfeited their monetary sovereignty by adopting the Euro. By doing so, they have given up their fiscal, monetary and exchange rate policies and in effect became little more than local authorities. Now markets, not politicians dictate the rules. The Maastricht criteria became redundant, if they ever mattered at all, as the inventor of the 3% budget deficit concept, Guy Abeille, a former senior French Budget Ministry official has recently acknowledge:

"We came up with the 3% figure in less than an hour. It was a back of an envelope calculation, without any theoretical reflection. Mitterrand needed an easy rule that he could deploy in his discussions with ministers who kept coming into his office to demand money. [...] We needed something simple. 3%? It was a good number that had stood the test of time, somewhat reminiscent of the Trinity." (original version: French)

Contrary to the early 90's recession, in the present slump, monetary policy has been more

accommodative because this is now the responsibility of only one

Central Bank- ECB- and not several as back then. Nonetheless, the ECB has been

slower than other central banks in cutting interest rates as can be seen below.

This is mainly the result of its single mandate at it seems to work like a handcuff that

prevents the ECB from being proactive during swings in the economic cycle. The problem now was that the rates were

already low to start with and even if the ECB had acted more swiftly, there was only

so much it can do as nominal interest rates cannot go below zero-the zero lower

bound problem- therefore, the room for conventional monetary policy to stimulate the

economy is more limited now than in the early 90's recession. However, once again, other central banks have

been more proactive and have been experimenting with unconventional measures to

stimulate the economy while the ECB has been more timid.

In a recession, when unemployment is increasing and monetary policy has lost

traction, only deficit-spending fiscal policy can effectively lead the economy

out of recession as Keynes explained a long time ago (audio recording). In this situation, the difference between the Euro

economies (non-sovereign) and other major economies (sovereign) becomes all the more evident. While initially both groups let their budget deficits increase, it is clear that

in the sovereign countries the increase was greater and longer. In the Euro economies the

increases were not only smaller but by 2010 this countries were already reducing their budget deficits while unemployment was still rising.

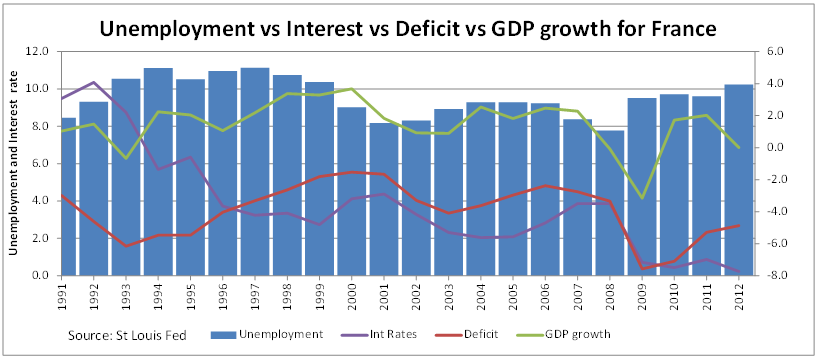

In France and Italy this is quite obvious, the more their unemployment increased the more they cutted. Keynes must be turning over in his grave. No surprise then that

unemployment kept on rising in the Eurozone while it started to fall in the other sovereign

countries. When comparing the deficits of the sovereign and nonsovereign countries for the year 2009, when this were at their highest, we can easily see that the US and UK were able to run deficits

of 13% and 11.2%, respectively, whereas France and Italy just 7.5% and 5.4%, respectively. Certainly this difference translated

into a couple of p.p. difference in the unemployment rate. By 2011, when the unemployment rate was going down

or at least levelling off in most sovereign countries, in the Euro area it

just gathered pace and at the end of 2013 it rose above 12%. Like the early 90's

recession this countries started to cut the deficit before unemployment started

to decrease. When it comes to

recessions, both the US and UK are quite Keynesians despite their reputation as neoliberals, while the Euro Area countries seem to have forgotten about the

"We are all

Keynesians now".

Again, while in the 90's the Euro

area countries had to cut their deficits because of the Maastricht treaty

limits, so they could join the Euro, in the Great Recession they had to do so

because of the limits established by the markets. As Randall Wray notes,

interest rates on government bonds for non-sovereign governments depend on

market assessment of default risk:

"the interest rate

on the nonsovereign, dollarized/euro-ized, government’s liabilities is not

exogenously set (whether it is a US state, a Eurostate or an Argentina). Since

it is borrowing dollars/euros, the rate it pays is determined by two factors.

First there is the base rate on dollars/euros set by the monetary policy of the

US government (the issuer of the dollar) or the ECB (issuer of the euro). On

top of that is the market’s assessment of the nonsovereign government’s credit

worthiness. A large number of factors may go into determining this

assessment. The important point, however, is that the nonsovereign government,

as user (not issuer) of a currency cannot exogenously set the interest rate.

Rather, market forces determine the interest rate at which it borrows."

This was the cause at the

epicentre of the Eurozone crisis. Back in 2001 when the

paper was written, Randall Wray defended that rates were converging because

markets were not pricing default correctly following the introduction of the

Euro:

"Markets, likewise, have not

yet fully recognized the regime shift that has eliminated currency sovereignty

for the nation states. While interest rates have not fully converged (and will not), they are

typically more similar than they had been before union. This is because

while currency risk has been eliminated, markets have not yet begun to fully

price- in default risk. Rating agencies are still treating the individual

nations as if they were sovereign, with eyes focused on the Maastricht criteria

(most importantly, the 3% deficit ratio limits)."

Although rates never fully

converged, as predicted, they came quite close to it. However, this came to an

end in 2007 with the onset of the recession when markets started to realize that not all sovereign bonds were equal. Given the severity of the recession,

deficits ballooned, in particular those of Greece and Ireland, and the markets started pricing the default risk, demanding a premium to hold debt from countries they believed were less creditworthy, making their situation even worst. These countries would later lose access to the markets, which led to the

intervention of the troika, and this would be known as the Eurozone crisis (timeline). All of a sudden markets views started to

matter more than the Maastricht criteria. This is an important change from the recent past because these countries are now

subjected to the more subjective appreciation of the market than to the more

objective Maastricht criteria. Moreover, markets are prone to have mood swings

and although these can happen at any time, they are more likely to happen when financing is more urgently needed.

The implications for this now non-sovereign states is that their ability to spent is now pro-cyclically biased. This is because during expansions not only taxes revenues tend to increase but market will also lend at more favourable terms, as their assessment of creditworthiness will certainly be more positive. The problem is that during recessions the opposite is true. Not only will tax receipts fall, but market assessment of creditworthiness will necessarily be more negative and as a result, governments will find it increasingly difficult to finance their borrowings or will do so at more unfavorable terms, making a bad situation worse as Randall Wray predicted:

"Meanwhile, the fiscal

situation of member states could deteriorate rapidly—with rising

market-determined interest rates absorbing ever- larger portions of the budget, forcing

spending cuts, driving growth further into negative territory, destroying tax

revenue, and leading to further downgrading of debt."

This was exactly what

happened to the Eurozone peripheral countries: Portugal, Ireland and Greece.

Having increased their budget deficits sharply following the onset of

recession, in some cases to rescue their banks, soon the markets started to

doubt the sustainability of their debts, resulting in higher yields, which in turn

made their debt even more unsustainable. They rushed austerity budgets in a

last effort to please the markets but they would eventually lose market access

and had to be bailed out by the Troika. The loans came with very strict goals in terms of budget deficit

reduction, therefore, these countries had to implement measures to reduce their

deficits, either by increasing taxation, reducing spending or both. Other

countries, namely Spain and Italy, feeling the heat of the markets embarked on

their own austerity measures, as did France, to a lesser extent.

Germany did not increase

its deficit much with the crisis and it's now even back to a balance budget. In this case, unlike the other Euro area members, unemployment has been falling

since 2005 and so there's no pressure whatsoever to increase the budget on

account of unemployment. However, this

fall in unemployment has little to do with its economic situation and more to

do with its demographic

nightmare. Germany has passed the point of no return and thus, bar any major

recession that affects its major trading partners, it will suffer from

permanent shortages of labour and unemployment should continue to fall for the

foreseeable future. This must be the case; otherwise, how can it be understood that an economy whose

growth has averaged 1% in the last decade and whose GDP shrunk more than 5% in

2009 has anyway halved its unemployment since 2006? On the contrary, in the

other countries of the Euro area unemployment has more than doubled from already

high levels.

If in Spain and Ireland the unemployment accelerated clearly from 2007 onwards with the burst of their property bubbles, in Portugal, Greece and Italy it went up more markedly at the time governments started to implement austerity measures. Even though part of the initial increase in the deficit resulted from the slowdown of the economy and subsequent unemployment - fall in tax revenue and increase in unemployment benefits -, a big part of it was directed to supporting financial institutions. If this was more evident in Ireland and Spain, it was nonetheless the case for Portugal and Greece, where part of their bailouts were destined to prop up financial institutions as well. The problem being that this spending had no direct impact on the real economy or employment. If part of that money had been direct into a stimulus package, like the one approved in the US in 2009, the unemployment situation wouldn't be as bad as it is. However, instead of stimulus packages, these countries were soon implementing austerity measures, making a bad situation worse, with unemployment reaching levels only seen during the Great Depression. In Ireland, Spain and Greece unemployment increased threefold from its pre-recession levels.

The markets effectively forced these countries to cut theirs deficits, which constitutes a clear departure from the previous status quo that had governed these countries for decades. If in the 90's they had abdicated part of their monetary sovereignty when joining the EMS, now they have clearly surrendered the rest of their monetary sovereignty as they have abdicated their national currencies and have become effectively non-sovereign countries, similar to US states. In fact, in monetary terms, one should not think of these countries as similar to the US or the UK but the equivalent to US states (See rankings). Just like them, Euro Area countries are now exhibiting a pro-cyclical behaviour that is common to non-sovereign states or local authorities.

While for Europe it’s

normal to look at the economic indicators at the country level, for the US there's a tendency to look exclusively at the federal level, as a result, there's a predisposition to overlook

how diverse the picture is at the state

level. Although in the Great Recession unemployment rose across all states, the

size of that increase was very different among the states. It affected in particular states with bigger

decreases in housing prices and with larger households in-immigration rates, namely Florida and

Nevada. This is exactly the same situation as Spain and

Ireland in the Eurozone, which not only experienced the biggest fall in house

prices since the recession but whose growth prior to the recession was for the

most part driven by immigration. If unemployment, at least initially, rose more steeply and across the

board in the US, it peaked in 2010 and has since started to fall steadily; Nevada with 13.8% had the highest rate of unemployment among all states. On the contrary, in Europe it increased more slowly and only in the countries affected by the housing burst before 2010; however, with the onset of the Eurozone crisis, unemployment started to surge in Portugal and Italy; and to shot up in Greece where, together with Spain, it peaked in 2014 above 25%.

In the US all

State governments, with the exception of Vermont, are required to balance their

budgets every year regardless of

the economic situation. In actual fact, it is

practically impossible for revenues and expenditures to get out of balance, since expenditures are controlled by available funds. This are enforced mainly

through prohibitions to carry forward deficits to the next fiscal year and by

restricting the financing of deficits through borrowing. Current expenses are rarely

financed through the issuance of new debt which is mainly used to finance

capital spending. This necessarily makes state spending pro-cyclically biased:

in economic expansions, revenues increase more rapidly and the ability to

borrow is increased as well because markets will tend to have a more favourable view

regarding state’s repayment ability, as a result, spending is likely to increase

fuelling economic expansions. On the other hand, when the economy slows

revenues decline, as states are required to balance the budget, they have to

cut spending, increase taxes or a combination of both. Depending on the

severity of the recession and the fall of tax revenues, fiscal consolidation

might act as a further drag on the economy and ultimately drag the economy into

a downward spiral, with less revenue being followed by more cuts

that in turn make the economic situation worse, resulting in weak tax

collection and a new cycle of cuts in expenditure.

Most of the times the recession is short and job cuts are hardly necessary. However, the Great

Recession was different, not only because of its severity and length, but also because it came after a housing boom

that had ballooned budgets on account of property taxes; and when this evaporated,

revenues collapsed and states and other local authorities had no other choice

than to balance their budgets in the midst of a recession, as they can't

borrow to replace the lost revenue as Paul Krugman

explained:

"The answer, of course, is

that state and local government revenues are plunging along with the economy —

and unlike the federal government, lower-level governments can’t borrow their

way through the crisis. Partly that’s because these governments, unlike the

feds, are subject to balanced-budget rules. But even if they weren't,

running temporary deficits would be difficult. Investors, driven by fear, are

refusing to buy anything except federal debt, and those states that can borrow

at all are being forced to pay punitive interest rates."

Contrary to most Euro area

countries, US States and Local governments had large surpluses before the crisis

but when the recession came revenues plummeted. States and local governments

didn't rush to close their budgets deficits as for the most part they increased

or maintained their expenditure up until 2010. Nevertheless, even without reducing

expenditure, deficits started to improve markedly from 2009 onwards on the back

of increased revenues. In some cases the increase in revenue was more than 50%. This was the result of transfers from the fiscal stimulus whose main purpose, as Obama has

stated, was precisely to plug the

hole in state budgets:

"When I came into office and budgets

were hemorrhaging at the state level, part of the Recovery Act was giving

states help so they wouldn't have to lay off teachers, police officers,

firefighters. As we've seen that federal support for states diminishes, you've

seen the biggest job losses in the public sector -- teachers, police officers,

firefighters losing their jobs."

The fiscal stimulus

package, known as the American

Recovery and Reinvestment Act and estimated to be $787 billion when it was signed into law in

February 2009, disbursed part of the money by making transfers

to state budgets. This allowed many states to close their budget deficits even when they

were increasing their expenditure. It is estimated that in Texas, where

expenditure increased significantly from 2008 to 2010, the stimulus funds

received plugged nearly 97% of

its shortfall for fiscal 2010. However, by the middle of 2011 stimulus money started to run out and,

with the exception of California, all other states below started to cut their

expenditure for the first time since the onset of the recession. By 2012 more

than 44 states were reporting fiscal year shortfalls.

In the US, contrary to most

countries in Europe, states and local governments can lay off their employees

to balance their budgets; and this was exactly what they

did in the current recession and that is why employment in the US has not yet

returned to pre-recession levels. Although initially state and local

employment, which together represent more than 87% of the more than 21 million

public-sector jobs in the US, rose when the private sector was already

shedding jobs and peaked around August

2008 but, has since been declining. If the stimulus package

has not increased state and local employment it certainly avoided that many state

and local employees were laid off, but

as it started to die out, state and local governments started to shed employment

at a faster rate, as Matthew O'Brien noted, state and local governments went on a

cops-and-teachers firing spree the likes of which we've never seen before. (See this report

for state variations).

While Greece has become the

poster child of "fiscal irresponsibility" in the Euro Area, it is

hard to say the same of Ireland and Spain, both of which maintained budget

surpluses for several years before the crisis, resulting in lower debt

stocks. In fact, on the eve of the Great Recession, both countries had one of

the lowest, if not the lowest, debts stock of any OECD countries. One can even argue that Ireland and Spain

were as fiscally responsible as Nevada or Florida were. Yet, when the housing bubble

burst, the effects were quite different in the two groups. The subsequent

slowdown resulted in higher levels of unemployment, but while in

Spain and Ireland the unemployment benefits had to come out of their national

budgets, in Nevada and Florida this came out of the Federal Budget. In

addition, in the absence of a true banking union and a more fragmented baking

sector in Europe, Ireland and Spain had to bail out their respective banking

sectors at a great cost, whereas in the US the Federal government once again

pick up the tab (TARP program). With falling revenues

and increased expenditure, budget deficits increased significantly more in the

European countries than the US states. In Ireland, deficits ballooned from a

balanced budget in 2007 to 30% of GDP in 2010 and debt jumped from 25% to more than 100% of GDP; much of it a result of the

once-off bank bailout. In Spain the increase was more steady but it

has nonetheless increased significantly. On the contrary, in the US states of

Florida and Nevada budgets deficits increased briefly and in 2010 were already

balanced.

Increase in expenditure should result in increased economic growth but here

the quality of that expenditure was certainly a major factor in the reversal of

fortunes. Even if part of that increase in expenditure in Ireland and Spain was

the result of the increase in unemployment benefits, the lion share was

certainly directed to prop up financial institutions. If unemployment benefits

undoubtedly help sustain economic activity it is not clear that bailing out

banks has the same effect. While one can understand that failing banks might

worsen economic activity if it results in drying up of credit it is not certain

that alternative uses of the same money would not have resulted in a better

outcome. If Ireland had spent 30% of its GDP(some estimates put

the total cost of saving the banks at 50% of GDP) in a multi year stimulus

package, US style, rather than propping up banks it surely would have been

enough to bring the economy back to life. It could even have engineered a boom. The US stimulus

at 7% of GDP would pale in comparison. Anyway, it could have something to show for in much needed

infrastructure. On the contrary, US states used the stimulus money to start

shovel ready projects that certainly helped to stimulate the economy and

increase employment.

Euro states and US states responded very different to their fading fortunes. To start

with, with the onset of recession and the subsequent increase in unemployment,

the automatic stabilisers - like unemployment benefits- kicked in, but whereas in

the Euro Area individual countries have to foot the bill, in the US this is the

responsibility of the Federal government. In addition, many Euro Area states had to bail out their national banks

(IMF estimates), while in the US this is

clearly the responsibility the Federal government. If Nevada or Florida had to

bail out their banks, they would more than likely go bankrupt. The result was that in the Euro States most

affected by the crisis deficits and debt rose more sharply than US states, to

the point where markets started to see some of the Euro states as default

risks, demanding higher rates, and in the case of Ireland refusing to finance

it altogether. Ireland and Spain had to adopt austerity budgets when the

recession was gaining speed while Florida and Nevada only had to do so when the

economy was already recovering. So it should not come as a surprise that

unemployment exploded in Ireland and Spain while it started to decrease in

Florida and Nevada. But in the end, the main difference in the response to the

crisis was that when the States and local governments in the US were in need,

the Federal government stepped in with significant transfers to their budgets,

while in the Euro area, in the lack of an established mechanism of transfers,

Euro states, to avoid bankruptcy, had to cut spending or increase taxes in the

middle of a recession and ultimately, as that did not work, they had to be

bailed out by other EU countries.

The Federal Government not

only paid for the increase in unemployment insurance, bailed out banks and

assisted State and local governments, measures that helped to sustain

and create many employments, but it also

created jobs directly. Federal government employment, with 2,736 million jobs represents 13% of all public employment in the US, increased

steadily the during the recession when the private sector was destroying jobs and it only began to

decrease when the private sector was already increasing employment. More than

600 thousand federal jobs were created until May 2010 as a result of the

stimulus package and the once off decennial census. Despite helping to save or

create an estimated 1.6 million jobs

a year for four years, the stimulus package came under attack and was deemed a failure, which

has in effect shut down the opportunity for further stimulus measures. The immediate consequence of the scale down

of the stimulus programme is that public employment began a long decline and

it's now even below its pre-recession levels. As Matthew O'Brien demonstrates in the following graph, the Great Recession recovery has the worst record for

government job added since the post war.

Despite that fact, the US

unemployment situation, like that of the UK and Japan, compares favourably to

that of the Euro area countries. Unemployment did not rise as high as in the

Euro Area and it started to came down sooner as well. This was ultimately the result of better

monetary and fiscal policy implemented in the US vs Euro Area. If on the monetary side there were some

differences in the response to the crises, with the Fed responding quicker and

more aggressively than the ECB, it is unlikely that this accounts for the

difference as lower rates don't necessarily translate into higher demand and

lower unemployment. On the other hand, the increase in government spending, increased demand when it was faltering and in that way sustaining employment in the US.

While in the Euro Area the

deficit of the Euro countries taken as a whole reached 6 % of GDP in 2009, in

the US it surged at 13% for the same year, more than the double, and by 2012

when the Euro area deficit had been reduced to below 4%, in the US it still remained

above 8%. Certainly this made a big difference in terms of growth and

unemployment.

It's here that the flaws of

the European arrangement became evident. While the ability of the Europeans

nations to implement counter-cyclical measures to smooth the business cycle has

been curtailed in the same way of US states, no supra-national or Federal

government has been created to take on the responsibility to pursue growth and

full employment policies as is the case in the US. This is a fundamental difference as Randall Wray explains:

"In the US it is the

federal government (the sovereign) that ultimately has the responsibility and

the means to maintain full employment—not the individual, nonsovereign, states.

Logically, this is a necessity implied by the fiscal arrangements. As the sovereign issuer

of the currency, only the national government is able to spend without regard

to revenue. Fiscal transfers (mostly from the US Treasury, although the

Fed can also play a role) from Washington to the states can help counter the

pro-cyclical behavior of states."

The fundamental problem with the Euro Economic and Monetary union is that nobody has the responsibility and the means to maintain full employment; i.e. the one who has the means has no responsibility and the one who has the responsibility has no means. In practice, given that there's no de facto government, just the ECB, the sovereign issuer of the currency, has the means but by no means has it the responsibility or even the legitimacy to maintain full employment. On the other hand, the national governments of the Euro states have the responsibility but limited means. Before the Eurozone crisis many governments behaved like they still have the means, and that was part of the problem, but have since began to realize that they are not sovereign, even if they don't fully comprehend the implications. The problem is that now many have started to believe that they were always nonsovereign. More worryingly still, is that the electorate still sees the national governments as sovereign, even if they nowadays resemble more local authorities, as a result, they believe that government have the same responsibilities and means they had before joining the Euro. By holding them accountable for their incapacity to improve the economic situation, in particular unemployment, they are wrecking havoc to the traditional party system in Europe with unforeseen consequences.

Therefore, if this countries are ever going to get out of the present economic malaise, there must be a marriage or remarriage of responsibilities with the means to maintain full-employment. This can be achieved either by creating a Central government for the Euro area or the Euro nations must reclaim their powers to issue their national currencies. The fact that this has not happen or is not even discussed just shows how little is understood about the causes of the Euro crisis. Otherwise, by keeping the current status quo, the countries in difficulty in the Eurozone will suffer from never-ending austerity. Eventually they will arrive to the conclusion that the problem with the Eurozone is the Euro and break free from the its straitjacket.

Sadly, this is not a guarantee, as Wynne Godley's conclusions 22 years ago in the article Maastricht and All That, can attest:

"I sympathise with the position of those (like Margaret Thatcher) who, faced with the loss of sovereignty, wish to get off the EMU train altogether. I also sympathise with those who seek integration under the jurisdiction of some kind of federal constitution with a federal budget very much larger than that of the Community budget. What I find totally baffling is the position of those who are aiming for economic and monetary union without the creation of new political institutions (apart from a new central bank), and who raise their hands in horror at the words ‘federal’ or ‘federalism’. This is the position currently adopted by the Government and by most of those who take part in the public discussion."